Caught in a Tiny Snow Globe

An Interview with Artist Elizaveta Porodina

, August 21, 2024

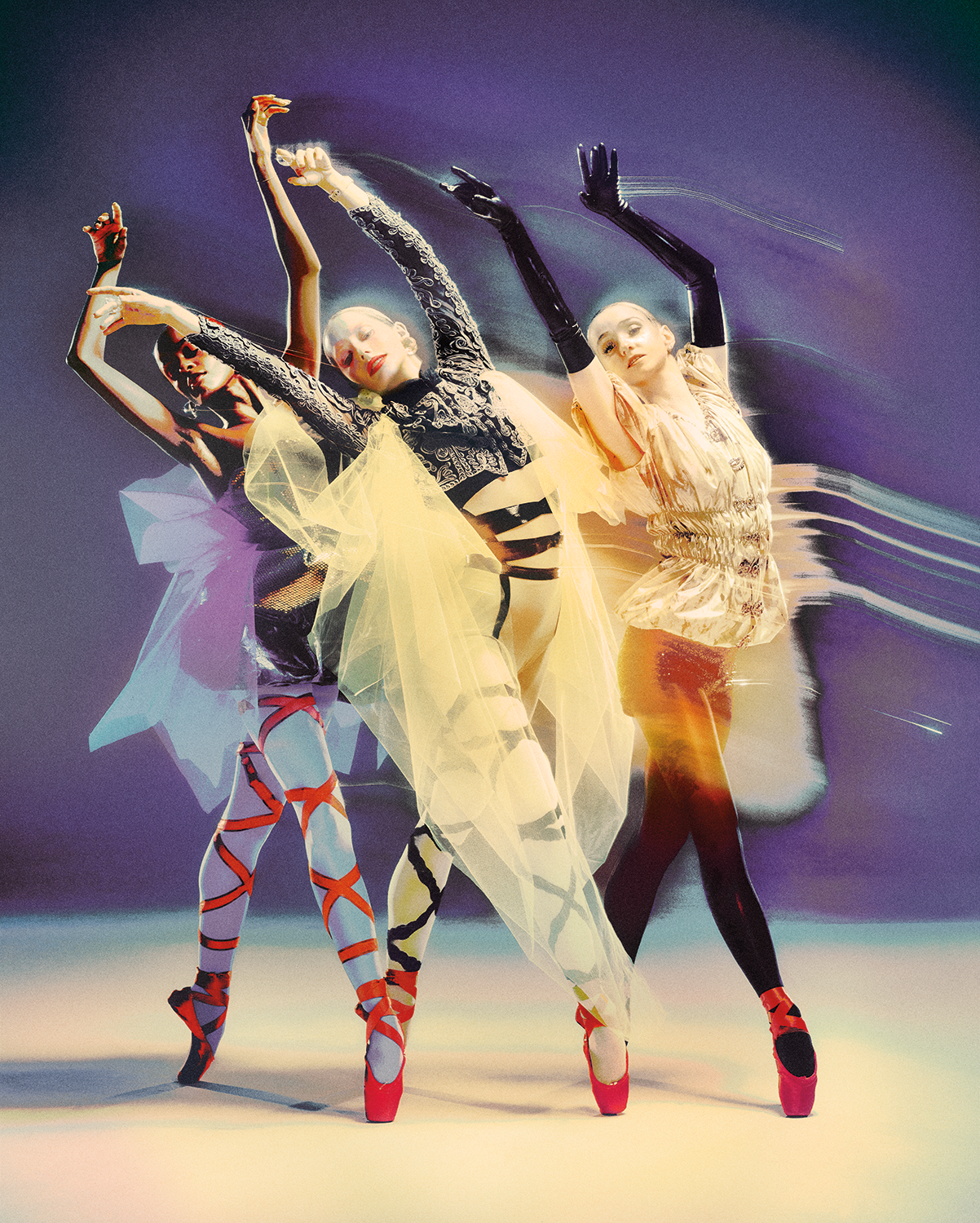

Each year, New York City Ballet collaborates with an artist to create a body of work that celebrates the Company's and the dancers' artistry in a new or unique light. This season, artist Elizaveta Porodina worked with Associate Artistic Director Wendy Whelan, Repertory Director Craig Hall, House of Iconica, several Company members, and a team of indispensable artists and technicians to create a moody yet effervescent portrait and film of NYCB dancers.

Porodina's singular body of work includes projects with Condé Nast, Louis Vuitton, Elle, and Numéro; she has exhibited with OstLicht Vienna, Foam Photography Museum, Münchner Stadtmuseum, and more. Her photography draws from a wide array of visual and personal inspirations, as well as childhood memories and her background in clinical psychology. We spoke with her recently to learn more about her creative process and the vision behind Ballet Unbound.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Please tell us a little bit about your background.

I'm an artist, a photographer, and a clinical psychologist. I studied clinical psychology, and did that until I was 25; then I switched to being a full-time artist, and I chose photography as my medium. I'm an autodidact. And if I had to describe my style, it would be experimental, cinematic, and inspired by paintings, visual art, cinematography, and narrations.

My colleagues were explaining that you use in-camera effects, on set, to create much of what might be assumed to be done in post-production. Can you explain why you prefer to go this route?

Obviously, in the resulting photographs, it is an effect. But I'm not doing anything for the sake of the effect. The photography is not done to present a cool trick. It's about a soul, emotions, the imperfection of being human. The things that happen in the process of creating and co-creating with another human are imperfect by definition, and I want to catch that. I want to catch a moment of authentic collaboration on every layer. One of those layers is the performance, and capturing it from my own, unique perspective—that's layer number one. Another layer is my way of seeing it. That could be the colors, that could be the clothing chosen together with the team, and all of those things. But there should also be another layer, in the visual sense, that captures the idea of how profoundly beautiful it is that there is always a uniqueness and a singularity to one moment of performance—which can be imperfect, and perfect because of that, and because of letting go of control. This is counterintuitive to an artist who’s a perfectionist, like I am, or a perfectionist choreographer or dancer, like Craig [Hall] or Wendy [Whelan] or all of the dancers. They are so focused on being flawless and amazing, and they perform in the most technically perfect way. So if I was perfect, and they were perfect, it would just be boring. It wouldn't be human. It would be produced by a machine. And I don't want that—I want to show that it's profoundly human.

How does this approach affect the dynamic on set?

How does this approach affect the dynamic on set?

Overall, I thought that it was two days of complete bliss. It is such a privilege to meet people who are striving for so much greatness, and to show everything they’ve learned about themselves and about their craft, and to capture their unique perspectives. We were working with a lot of dancers throughout the day, then pairings, and collaborating with Craig and Wendy at the same time, sharing their perspectives on the dancing and on the movement. It was fascinating because it was truly a collaboration between everyone, which is, as you can imagine, challenging. Working with just one person can be quite challenging because you're really holding the threads between yourself and the other person. You're trying to capture everything—you're trying to get all of the information and the truth, the authentic part of that information. Where is the truth? Where's the reality in it? And where is their human story in that? At the same time, you want to get their perspectives. I was asking Craig, Wendy, and the dancers, for example, “What part of this choreography could represent what I'm feeling, here in the room, right now?” And I was asking this constantly. Then I add my interpretation, and something completely new arises. So it's really a collaboration of their visions, my vision of that, and my reaction to it in real time.

Do you have any history or interest in dance or ballet in particular?

In my childhood, I was introduced to theater, ballet, opera, this entire world in a very casual, nonchalant way, so I didn't develop a sort of frightened respect or distance from it. I was watching it with pleasure and delight from the very beginning. I knew of people like Anna Pavlova and Maya Plisetskaya as role models, in terms of performance, very early on. Later in my life, I was introduced to people like Pina Bausch, and other traditions of dance from other cultures, like Butoh and Gaga. I am very interested in ballet, and always have been, but my interest is not limited to that specific kind of dance. I think this is where it becomes interesting—I think this is where the choreography is going, and where the openness of New York City Ballet is going. It's very forward-thinking.

Were you thinking a lot about dance in particular as you went into the studio?

What I didn't want was to create photography that would be expected, or would be too conforming to tradition. There are other people who can do that. You should always ask yourself, “What is it that I can bring to the table and that only I can do?” My forte lies in the authentic, live reaction. I did watch the choreography in advance, but I tried not to be directed by it, because then it would just be a reinterpretation of what was already there. I also tried to create something new on set with all the people present.

As an artist who is capturing something, and as the artist who is in front of the lens, you cannot avoid self-portraiture. It's impossible. You always bring yourself in, no matter how much you try—especially when you're trying to avoid it. I'm not trying to resist it. I make myself very vulnerable that way, there is nothing I want to hide. This is the big difference from the classic form of ballet photography—it can be very much about perfecting a certain technique and showing off that specific technique, and then everything else is sort of secondary—the photography part, or maybe the truthful, emotional part. What I wanted to bring was the deeper psychological level of my storytelling.

Were there any other inspirations or ideas you had in mind as you prepared?

Honestly, a lot of them. It is eclectic in the sense that I couldn't pinpoint a specific one. The creation of original costumes for the shoot was really noteworthy. I worked with the amazing House of Iconica, who designed the costumes and handled the live creation of the costumes on set, because a lot of pieces were prepared and the designer was reacting live to the dancers and to their auras and energies. They really went above and beyond, spending months and months collecting the inspiration and creating the vision of what this could be, based on my instructions and how I saw the movement. The way I briefed everyone in the beginning was that I wanted the movement to be physically visible. I wanted the tunnel of time truly created by the clothes, so that you see where the person was in the past and, when they're moving to the future, the vector of their movement is visible. That's a collaboration between a photographic technique and the costume design. And it was all created specifically for that purpose. It was so beautiful to watch; it's something truthful while also playing with the elements of camp and kitsch, capturing this sense of a person caught in a tiny snow globe, which is a key element of my work, too—nostalgia and fascination with elements from your childhood, and infatuation with magic and magical things.

Was there an emotional quality you were trying to capture or express?

I always try to react to what I see and give a twist to it. If I see someone who presents themselves as physically strong, and emotionally tough, I want to see their tender side. I want to take the moon that’s illuminated on one side and turn it a little bit to present the other side that seems more twisted, more unstable, more tender. I think that's what happened with most of the subjects; obviously, you still see their physical strengths—these are some of the strongest, most amazing athletes I've ever seen, physically and mentally, and in the way they command and will their bodies to do these impossible things. It could be so tempting as a photographer to just capture that and to say, “Look how incredibly these people are built.” I want to let a certain tenderness and vulnerability seep in. I don't want to single anyone out, but, for example, working with someone like Emily Kikta, you look at her and she's so funny and strong and tough, and then she comes on our stage, and there is so much tenderness, almost like she's a child in a way, like she's discovering the movement for the first time. That is so, so fascinating to me, and I think that's what really makes the difference—an incredible artist and someone who's learning that there is an ability to let go and look at the movement with fascination.

Can you tell me how you came to take on this project?

Can you tell me how you came to take on this project?

In 2020, during the lockdown, I had developed a technique of working with people long-distance over Zoom; it was a new photographic technique that I was playing with and that I really wanted to become a part of my aesthetic. In the frame of that long-term experiment, Wes Gordon of Carolina Herrera asked me whether I would shoot a campaign. So, we were shooting multiple dancers all over the world in Carolina Herrera clothing. The clothing was sent to them, and they were installing the backgrounds themselves, and experimenting with everything on their side. I was photographing it and directing from Munich. Wendy was one of the dancers, and I had the privilege to experiment and really play with her. We shot some amazing pictures that eventually landed in the book Colormania. I think we both thoroughly enjoyed the collaboration and wanted to meet each other in person and go further, see what we can do with other people.

Do you think that experience informed the way you worked with the dancers?

Wendy was there the whole time, and we talked about it constantly—we co-created the piece. But I think the biggest takeaway from that experiment was that it was a way to dial down. There are usually a lot of environmental elements in my work; I love set art, production design, and things like that. I love to create an environment for storytelling. When I work with dance, and when I work with people who express a lot through the body and through a set of directed movements, I think it can be very interesting to dial down these things that I'm used to and really tell the story through the body. I did even more of that here. There was just a studio, the color of the lighting, and the movement, embellished by the costumes.

Is there anything else you’d like to share about this experience?

I was in love with every single one of them, truly. I was just completely infatuated. And it was such a pleasure working with Wendy and Craig on this as well, we really bonded as people. I was so honored by the trust from the Company's creative services and media teams led by Camille Aden and Laura Snow—there was a lot of freedom, all the freedom that I could have wished for.